Vega Sicilia: 150 years of legendary winemaking

Spain’s most prestigious winery, once favored by Churchill, among others, refuses to increase output

Close the door and turn down the lights. The hustle and bustle of the outside world mustn’t disturb this unique experience. Isolation is required; at most, put on a little Bach. Breathe deeply: in, and then out. Bring the glass to your lips, look, sniff, and let yourself be carried away by the power of tannins that have been judiciously tempered by wood and the passage of time, then allow yourself a sip of a legend, an experience like being punched by silk, if such a thing were possible. Elegance and supremacy, velvet and lead: chiaroscuros, classicism, something close to perfection. Is there really such a thing as the fully rounded wine, one that leaves no room for doubt? The gods and Bacchus would say no; but this comes very close.

For the last 150 years, the great wines of Vega Sicilia have been revealing to their fortunate drinkers the whys and wherefores of a legend, the legend of Spanish enology – of enology, period.

Depending on the vintage, enjoying a bottle of its hallmark Vega Sicilia Único means spending at least €180, while a Valbuena will set you back around €100.

That said, in strict price-quality comparisons – not necessarily the way to judge this wine – Vega Sicilia is little short of a bargain compared to the great wines of France, Italy, the United States, or Germany. There are any number of Saint-Emilions, Pessac-Leognans, Beaunes, Napas, Barolos, and Sassicaias whose price-quality ratio does not come close to that of a Valbuena, an elegant, well-rounded wine, sharing many of the characteristics of the best Ribera del Dueros, with the structure of a great Bordeaux and the poetry of the complex, incomparable wines of Burgundy.

And not just Vega Sicilia…

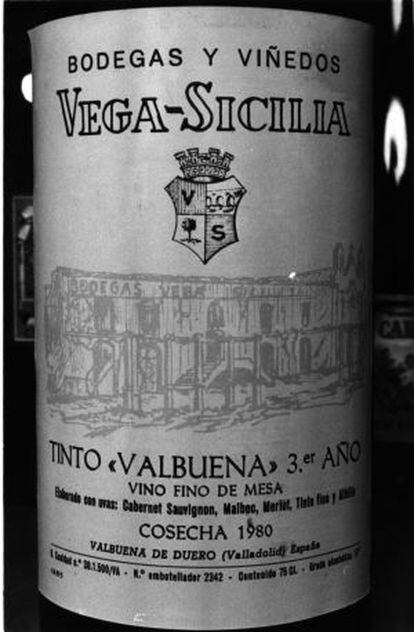

There are three key wines in the Vega Sicilia portfolio that carry the Vega Sicilia name: Vega Sicilia Único, Reserva Especial and Valbuena 5º. Alión (Ribera del Duero), Pintia (Toro), Oremus (a Hungarian Tokaj dessert wine), and Macán (a Rioja produced in a joint venture with Rothschild) are the company’s other brands.

The Vega Sicilia story goes back to 1864, when a Basque entrepreneur named Eloy Lecanda moved to Valbuena de Duero in Valladolid province and set up a winery. Today, Vega Sicilia’s vineyards cover around 985 hectares. Eloy Lecanda was a pioneer, deciding to plant new types of grape, such as cabernet sauvignon, malbec, and pinot noir.

After Lecanda went bankrupt, his groundwork was built on first by Txomin Garramola, who bought the winery in the early years of the 20th century: in 1915, the first Vega Sicilia and Valbuena went on sale, following the guidelines established by the great Rioja winemakers of leaving wines for long periods in wooden barrels.

In 1952, Vega Sicilia was sold to seed company Prodes, which brought in Jesús Anadón, an expert on Ribera del Duero wines, who established the region’s denomination of origin status.

“Jesús Anadón used to say that he couldn’t put his finger on it, but that there was something about this place, the climate, the soil, the vines, that all made for distinctive wines,” says the winery’s CEO Pablo Álvarez, adding that the key to Vega Sicilia’s continuing success is, “respecting the personality of the wine you make, regardless of the techniques used in the process.”

The Álvarez family acquired Vega Sicilia in 1982, almost by accident. David Álvarez, Pablo’s father, had been hired to act as an intermediary between the then owner, Venezuelan millionaire Miguel Neumann, and a group of British and Swiss investors. But David Álvarez saw his opportunity and, after paying the equivalent of €3.5 million, took over the company.

Since then, the family has been involved in a legal dispute worthy of Falcon Crest that has pitted David Álvarez, his father, and two of his children, against his five other children. At stake is control of Eulen, a global outsourcing group. “It’s an unfortunate affair, and shows no signs of being sorted out, but it happens in a lot of families, but because we are well known, there is a lot of media coverage,” says Pablo Álvarez.

But the family was at least able to put its differences aside to celebrate Vega Sicilia’s 150th anniversary, organizing a series of lavish dinners at the winery’s cellars in Valbuena de Duero attended by more than 1,000 guests and prepared by celebrity chefs such as Juan Mari Arzak and Joan Roca. Among the guests were the owners of other legendary wineries such as Château Yquem, Gaja, Cheval Blanc, Mouton Rothschild, Osborne, and Marqués de Murrieta.

“Vega Sicilia is a legend, but it is also amazing that there are not at least five other wineries with a similar status, as there are in France, for example,” says Pablo Álvarez. He says that his favorite Vega Sicilia is the 1999 Único: “a marvelous wine that proved very difficult to produce, perhaps that’s why I find it so satisfying. But I would also choose a ’94, which is also exceptional.”

The winery has not increased output over the years, and continues to produce around 330,000 bottles a year, of which no more than 130,000 are labeled Único. Exclusivity means imposing limits on who can sell it: around 4,500 establishments worldwide, and each client is allotted a certain number of bottles. Over the years, the wine has won the admiration of connoisseurs such as Winston Churchill, and more recently, singer Julio Iglesias. Demand usually far outstrips supply; and of course if the harvest isn’t of sufficient quality, as happened in 2001, then no Único is produced. That’s the price of a legend.