“Falciani’s future isn’t going to be decided in a Spanish court”

French public prosecutor Éric de Montgolfier discovered the HSBC tax evasion whistleblower’s encrypted files in a small town in southern France

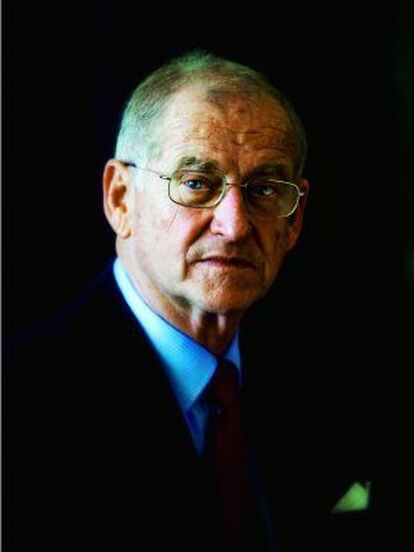

French public prosecutor Éric de Montgolfier has got up at 3am to travel from his home in Bourges, a quiet provincial town in central France, to Paris. He then had to catch a plane to Madrid so that he could give testimony in a hearing to decide whether Spain should extradite Hervé Falciani, the former HSBC employee, to Switzerland. That is where Falciani is facing charges of stealing the details of tens of thousands of bank accounts — data that Spain and several other EU countries have used to pursue suspected tax evaders.

The court ruled against the extradition request, saying that the charges Falciani faces in Switzerland — including unauthorized obtaining of data, breach of trade secrecy, industrial espionage, and violation of banking secrecy — are not considered crimes under Spanish law.

Falciani admits taking the data, describing himself as a whistleblower against what he describes as "scandalous" practices at Swiss banks.

He first fled to France in 2009 after HSBC identified him as the source of the data leak. In July last year he traveled to Spain, where he was detained on an international arrest request triggered by the Swiss warrant. He had received a conditional release from custody in December, ahead of the extradition proceedings.

Montgolfier's testimony was key to the court's recent decision to reject Switzerland's extradition order. The 65-year-old, who is married with three daughters, and who often travels to work by bicycle, discovered the encrypted files taken by Falciani at the former HSBC employee's house in Castellar, a small town in southern France. It was these files that have enabled German, French and Spanish prosecutors to recover hundreds of millions of euros from tax evaders. Spain alone has so far clawed back 250 million euros thanks to the whistleblower.

It has been a complex case, one that Montgolfier initially undertook alone, further consolidating his reputation as an independent-minded prosecutor prepared to say what he thinks, and who has long been a thorn in the sides of bankers, politicians and justice ministers in France.

Over the course of his career, Montgolfier has put many famous figures in the dock, among them Bernard Tapie, a former Cabinet minister, financier, and ex-chairman of Olympique de Marseille. Along with most of the club's board, he was found guilty of match fixing in 1993 and was given a jail term. "Without this affair, Montgolfier would be unknown. If the only thing he has risen to after 25 years is a public prosecutor, he can't be up to much," said Tapie at the time.

He was wrong. Montgolfier's credibility was boosted to the same degree that Tapie's was driven into the ground, as he would be later implicated in several other financial scandals. During his 10 years as chief public prosecutor in Nice, he investigated several members of City Hall, while criticizing the friendships many of his colleagues had with senior local politicians.

After giving his testimony, but before the court made its ruling, Montgolfier agreed to talk to EL PAÍS.

Question. Have you talked to Falciani?

I'm not sure the English have a European bone in their bodies"

Answer. He greeted me, but I didn't recognize him

[the former HSBC employee appeared in court wearing a wig, glasses and makeup].

Q. How was your testimony?

A. Fine, I'm still alive. It's the first time that I have been in a Spanish court. Trials here are different to those in France.

Q. Were you surprised that Falciani called you as a witness?

A. No, because I am among those who can establish his role in the discovery of the documents and as regards the help he has given us.

Q. Do you think that Falciani's life is in your hands?

A. It depends on the judges. I have provided some information, but Falciani's future isn't going to be decided in a Spanish court. He has betrayed the interests of a large bank and will have problems finding employment in the sector. I am a witness, and nothing more. When I heard that he had been arrested here at Switzerland's request, I told myself that it would be unjust for him to be extradited.

Q. Is it true that that without his help it would not have been possible to recover HSBC's secret information?

A. It would have been much more difficult. He helped us to access the computer, which had been encrypted. There were parts that we would not have found. Falciani provided them. His help was vital.

Q. What is your opinion of Falciani? Would you describe him as a hero, or a thief, as the Swiss charge?

A. I don't know what to make of him. Initially I said that he was rather messianic, that he has something to contribute to a world immersed in a financial crisis. I am not sure it's that simple anymore. There is undoubtedly part of this that is true, but there are things that happened before he was arrested in Nice that are less clear. I don't know what he did, what he wanted to do. There are episodes in his past that are open to discussion.

Q. Something he would prefer to remain hidden?

A. Before he was arrested in France there was an episode in Lebanon that I am not sure about. I think that he tried to sell the information to a Lebanese bank, but it rejected the offer. Yes, there are areas that are shadowy in this affair. He did not try to sell his information in France. Whether he tried to do so in other places, I don't know. If he had obtained money from all this, he would not be in the financial situation he appears to be in today. His lawyers say he is having difficulties. When the Swiss authorities asked to search his house, his lawyers did not tell them what was in Falciani's house. We thought that it was a routine request. But when the Swiss federal prosecutor arrived in Nice we thought he had come for a holiday. We later learned, not from the Swiss, but from Falciani, what was going on. The Swiss were not open about what they were doing.

Q. What did you think when the French police told you that he had data on some 130,000 potential tax dodgers?

A. I thought that this affair was too big for me to handle on my own. This is one of the biggest tax-evasion cases ever. The French president has just announced the creation of a national anti-corruption investigation unit. With hindsight, perhaps we could have done with one sooner.

Q. Did you come under any kind of pressure from the French government to return the files unopened?

A. There are two ways a prosecutor can work: ask the minister what to do; or do what one thinks is right. I didn't ask the minister, I opened the investigation without asking for an opinion. I don't know whether I would have been told not to. I knew that I had to carry out this investigation. There was no pressure. [The matter was eventually put in the hands of the Paris Public Prosecutor's office, with Montgolfier retaining control over the investigation in Nice.]

Q. Did the banks try to pressure you?

A. The management of HSBC did not want us to investigate the accounts. Neither did Switzerland. Many Swiss told us that we had no right to undertake the investigation. I received some unpleasant emails from the Swiss federal prosecutor, but that is not important.

Q. What has been the most difficult aspect of the investigation?

A. The feeling that I did not know what was really going on. We applied criteria to try to organize the mass of information we had, and which would have filled two train carriages if printed out on paper, but we really didn't know if we were overlooking more important information. Even when we had the list of 8,600 French customers, that didn't mean that there might not be more French people involved via front companies. And it's the same in Spain. I don't think that Spain has found everybody. It might well be that there are Spaniards hiding in the French list, or involved in companies that haven't been investigated yet. We need a European public prosecutor to deal with cases like this. I think that is viable. There are many people involved in this, and not just Europeans, but people from Canada, from the United States, and even Arab nations. Each country needs to take care of what affects it. That is why France was justified in keeping the information and distributing it to the affected countries. It sent information to the Italian and German tax authorities. Not many countries have asked for access to the information, and I don't understand why. I even rang a friend in Belgium telling him he should look into it, but I never received any request from the authorities there.

Q. What did it feel like to have the private information of so many people in your hands?

A. This is a nice case. The life of a prosecutor is usually about small affairs: accidents, theft, crime. You believe that you are going to be genuinely useful. I imagine the feeling is the same for a journalist who uncovers something and thinks that it will serve a purpose. Sure, sure! We were fascinated by the importance of the case, but at the same time we were saying: Careful! It has to be real. As in journalism, one cannot make mistakes. I remember the false case that former President Sarkozy was involved in. I told myself that I needed to be careful and to make sure that everything was true. Almost all corruption cases lead to tax havens, many of them in British territories.

Q. Why do you think that this unfair and scandalous system continues to survive?

A. I am not sure that the English have a European bone in their bodies. They have a very selfish outlook. I am surprised that the countries of Europe agreed not to do anything that might be seen as against the interests of another member state. The banks have a huge influence on national economies. We need to close the banks in Switzerland that refuse to provide information about their customers. The problem is replacing them. It's like telling South American countries to stop producing drugs. If we ask them to give up that part of their economy, what do we replace it with? We'd have to offer them another way to survive. Hollande says that he is determined to close down the tax havens.

President Hollande says he is determined to close down the tax havens"

Q. Do you believe in those kinds of statements?

A. He is the president of the republic! The crisis currently affecting France is so serious that something has to be done. I have noticed over the years that things tend to work like graphs: when things hit a peak, something is done about it. Today we are talking about corruption, tax evasion, HSBC. We talk and we talk, and the thing hits a peak, and then, puff! we stop talking about it. I hope we don't stop talking about something as important as this. Our institutions need to be stronger, we need to give them the resources and put people in positions of leadership who want to get things done. We have to create organizations that really help fight corruption. But history makes me doubt whether this can be done. French Economy Minister Jérôme Cahuzac, a Socialist Party member, who was sacked recently for having a secret account in Switzerland, as well as the Reyl bank, are just the most recent of many scandals involving French politicians.

Q. Are there any more secrets involving leading figures in French life to be uncovered in this affair?

A. There are secrets everywhere, but in the banking system, rather than secrets, there are a lot of shadows. We see it in our country, where politicians are asked to reveal their wealth, and the majority do not want to. I have no problem making a full declaration, because I can account for every cent. When somebody says that they cannot say how much money they have, I suspect that that person is hiding something. I am a prosecutor. There is nothing wrong per se in having a lot of money; the question is whether you can account for how you got it.

Q. What has been the most difficult moment in your career?

A. Every time I see that the insults affect those close to me, but aside from that I have had no problems. On the contrary, some people have helped me, have given me the strength to resist them. Under pressure, you either give in, which makes it hard to look at yourself in the mirror, or you resist and it makes you stronger.

Q. Has your work affected your personal life often?

A. Yes. But my family is ready for it. Either you bow your head, and there is no going back, or you remind yourself that you have a duty that you chose to carry out. It isn't about bravery, it's about honesty.

Q. Don't you believe that all judges and prosecutors should be honest?

A. It would be enough if they just did their job. If you suggest to them that they are knights in shining armor, they will tell you that is too hard. We have to ask them to deliver what they promised: justice. In my case the knight in shining armor thing was invented by the media. I know lots of magistrates who I wouldn't call knights in shining armor, but they are rigorous. And that is the only thing you can ask of them. When I was a young magistrate they used to tell me: slowly, your time will come, but if you ease up, you'll be easing up the whole time. Talking about my future, a prosecutor said to me one day: "Behave like a pimp and everything will be fine." He was telling me that by prostituting justice I would rise to the top. But that isn't very interesting. In general, most people don't believe in justice. Justice doesn't satisfy anybody. Not believing in justice seems normal to me. We are also mistrustful because we don't know it. Sometimes magistrates are not as good as we'd like. There are many things that explain why justice is so little appreciated. We admire the doctors who save us, but not those who kill us.

Q. In some ways you remind me of Baltasar Garzón, a former Spanish judge who fought against terrorism and corruption. He was punished for ordering illegal wiretapping of prisoners. You have also been accused of violating the rights of a prisoner.

A. I was found not guilty. Facing a tribunal to account for one's actions is not a scandal. But it would have been if they had found me guilty. I have brought proceedings against too many people to believe that I cannot be judged. When I left the court I said that it was an experience every judge in France should go through. I don't think that anybody found it funny. Garzón's case shows that if we are to bother the powerful we have to be absolutely rigorous, and even then we cannot be sure. You cannot make one mistake.

Q. You are due to retire in a few months. I can't see you spending your time riding around on your bicycle. Have you thought about going into politics?

A. Never! Never! It's been suggested to me a couple of times. They say that I am preparing my candidacy, but I wouldn't know how to. I have spent my time telling people what they have to do, reminding them of the law. I can't suddenly become somebody who says: "Hi, how are you? What can I do for you?" I wouldn't know how. I am literally incapable. There are many other things one can do aside from politicking: writing, for example. There are many things, but not politics.