Dissecting the Da Vinci codices

A National Library show of the great polymath's notebooks reveals his genius, complexes and fears

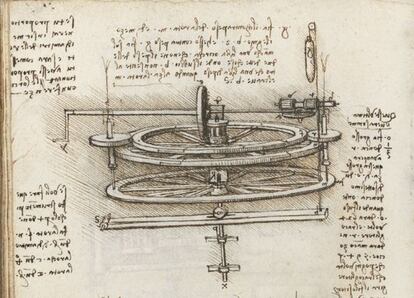

One night he ended up discovering how to square the circle. On another he would be at rock bottom because of an unhappy love affair. One day he catalogued the 116 books in his library - which included works by Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Aesop, Ovid, Pliny, plus manuals on herbs, anatomy, philosophy, cosmography and grammar - while another day he described the essential items in his wardrobe. For a commission he drew a map of Tuscany showing an imaginary diversion of the River Arno and a machine for crossing a mountain in a straight line. He drew connecting rods, cranks, pins, hinges and screws. At the same time he immersed himself in a world of springs and pulleys.

The great polymath of mankind's history, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519), also devoted all the time in the world to Marco d'Oggiono, nicknamed "Salai" (or, Little Devil, after a fashionable novella of the era), even if it was futile to try to tame the object of his misguided passion. When Da Vinci was part-paralyzed by a stroke, Salai offered all his paintings to the king of France - among them a small canvas that would become hugely famous - and fled back home with the money. Da Vinci remained in France, sick, impoverished and abandoned.

Elisa Ruiz, professor of paleography and official documents at Madrid's Complutense University, has reconstructed Da Vinci's life story without letting herself be swayed by imagination or myth. Naturally she hasn't read Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code, the plot of which is a harmless juggling exercise compared with the real life of an exceptional man who had more than his fair share of psychological issues. The illegitimate son of a notary and a peasant woman, he was an autodidact with no academic training and whose ignorance of Latin and Greek meant he was unable to access valuable works. He was also a homosexual, and was tried for sodomy, as well as being a perfectionist who constantly revised his works, never able to finish anything.

And he was also, adds Ruiz, "an influential man who upended scientific criteria and defended the experimental method; a non-conformist with modern ideas who would triumph many years later." In short, he was a genius born "before his time."

You can make out part of all this in El imaginario de Leonardo (or, The imagination of Leonardo), an exhibition running until July 29 at the National Library in Madrid. The library houses two valuable Da Vinci codices (christened Madrid I and Madrid II back in the 1960s), which, it says, represent 10 percent of all the written Da Vinci work preserved in the world.

Their market value is colossal: Bill Gates, the only individual with a Da Vinci codex of his own to enjoy, paid close to 20 million euros in 1994 for the 72 pages in which the great man immersed himself after finishing the Mona Lisa and showed off his limitless imagination by predicting automobiles and helicopters.

The Spanish codices (600 pages long, which is to say worth 2.16 billion euros at Gates' 1994 price) shot to global fame several decades ago when (untrue) news of their discovery announced at a Boston hotel generated a media storm. There is no proof that the two manuscripts have left Madrid since they arrived via the hand of Italian Renaissance sculptor Pompeo Leoni in the 17th century. One of his heirs sold them to musicologist, cleric and collector Juan de Espina in 1642, who subsequently bequeathed his archive to Philip IV.

What did leave Madrid, as Ruiz has just discovered, were the Windsor Collection drawings, in which Da Vinci extended his talent with scientific meticulousness: he dissected 30 bodies to perfect his knowledge of human anatomy. This series was sold to the British aristocrat Lord Arundel in 1646 as a wedding present for the Prince of Wales.

Da Vinci wrote the two works housed in the National Library in his later years. Madrid I is a treatise on statics and mechanics where he shows that his mental conception departs from an image to the writing that accompanies it, from right to left (he was left-handed), like a secondary element. "His lexicon is brief, poor and he sometimes writes lists of words to enrich it," reveals Ruiz. Each page is a universe in itself, where he tackles a question and resolves it.

Madrid II - the seed of A Treatise on Painting, which Francesco Melzi, Da Vinci's disciple, heir and the executor of his will, copied - has a technical section dedicated to the geometry, strengthening and reproduction of medallions. The essential piece is the cast of the horse designed for his patron Francesco Sforza. There is also another section, comprising personal notes, that are intimate enough to make you blush: "I will die if your morality prevents you from giving me a rub down," he writes.