The grim life of a galley slave

Restoration of Navy's Galleys Books reveals the harrowing stories of the captives who rowed the king's ships

In 1690 the standard price for a slave was 1,500 reales - a slave capable of rowing for hours, days or even weeks in the open air. But despite his 22 years, Maraut, "son of Yusuf, dark, with small mouth and thick lips, wart on his head by the ear, stain on right ear, sign of injury on the same hand," was sold for just 400 reales on account that he was "useless."

Being unfit and useless for combat must have helped the distinguished Cervantes avoid a similar fate to Maraut after he was captured on his way back to Spain after surviving a great many skirmishes and the greatest naval conflict between galleys in history: the Battle of Lepanto (1571).

Cervantes' adventures - five years held captive in Argel - do not figure in the 25 Galleys Books preserved by the Spanish navy because they cover a later period (1624-1748), featuring slaves, prisoners and enlisted soldiers and sailors. The restoration of these gigantic volumes will provide valuable information for the historians of today: written using the circumlocutions of the time, they reveal biographies of common people at the service of royalty.

"When the king needed rowers he provided incentives for [the courts to give out] galley sentences," says Carmen Téres, technical director of the navy archives.

For having deflowered María Rosa Borrell" in 1727, Josep Almarall got four years at the oars

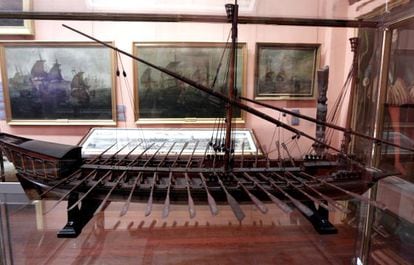

Maraut was one of the king's thousands of slaves - the brute force that propelled several almost flat boats, ideal for coastal skirmishes, around the Mediterranean. We do not know if leaving the galley bettered Maraut's life, but it is difficult to imagine conditions worse than those on board. A shackle kept him tied to his seat, where he ate, slept and went to the bathroom. He was barefoot and his head was shaved to prevent the accumulation of lice and to make identifying him easier in case he escaped. Nothing more lay ahead for a slave than the sea, battles with the boats of their (probably) Turkish or Berber compatriots, and the very real option of ending up at the bottom of the Mediterranean, trapped in their rocking prison.

"It is a mistake to try to judge that time from our point of view," says Pedro Fondevila, secretary of the department of Naval History at the University of Murcia. "In the 16th century people's main worry was eating. It's sometimes said you could recognize a galley by the smell that preceded it, but at that time almost nobody washed."

Each day the galley slaves received a piece of baked and stale bread called bizcocho, a stew of broad beans and a ration of water. Their chances of being freed were minimal: only if their masters won a battle or if they were exchanged for Spanish prisoners.

The story of the Algerian Amete was exceptional. Philip IV gave him his freedom on May 11, 1642 in a show of moderate magnanimity: "It has been more than 24 years that he has served me at the oar and finding himself at the age of over 70 and unable to continue, begging me, I do him the favor of ordering, and leaving another slave to do it for him, that he be placed at liberty."

Entered into the Galley Books were the slave's name, most outstanding characteristics and notable facts such as their freedom or their death. But it was not only slaves that filled the ranks of the common prisoners. "In Spain there were fewer slaves than on the French or Turkish boats," says Pedro Coll, deputy director of the naval archives. Of the 25 books, 18 correspond to prisoners, three to slaves and four to soldiers and sailors.

The volumes hold a magnifying glass up to 17th- and 18th-century society, which treated crimes related to money or certain sexual practices more harshly than murder. Francisco Giménez, "Gypsy, native of the land of Segura, son of Sebastián Moreno, both ears cut," was sentenced to eight years on the galleys for a crime. But Juan de Morales, 35 years old, "native of Utrera, son of Pedro, good constitution, white, blue eyes," was given 200 lashes and 10 years on the galleys for committing "the unspeakable sin" - which is to say, sodomy.

Catalan Josep Almarall was punished with four years at the oars "for having deflowered María Rosa Borrell" on January 13, 1727. Much more serious for the courts was the offense of Francisco Thomas Carnero, an 18-year-old from Málaga who was sentenced to 10 years on the galleys "for the act of bestiality he committed with a female donkey."